By M.B. Dallocchio, LMSW

*This is an article from the Winter 2021-2022 issue of Combat Stress

Veterans who are trauma survivors searching for a recovery method that fits them best may be viewed as warriors embarking on what Joseph Campbell described as the Hero’s Journey.1 Veterans experiencing post-traumatic stress not only have to navigate mental health stigma but find their path toward healing while managing various forms of trauma-induced symptoms. As a Combat Veteran, artist, and social worker, I have assisted others on their own Hero’s Journey – which was only possible because I had figured it out the hard way. I discuss this post-war homecoming odyssey in my memoir, The Desert Warrior.2

However, during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I relocated to London and created Veteran Art Studio3 on YouTube, which embodies all intersectional aspects of my experiences, what the journey has meant to date, and why it is important to broaden one’s horizons on the path to healing from military and war-based trauma. In a time of crisis, it became a priority to let people know that they weren’t alone, and that healing is certainly possible. I would argue that it is imperative to include the arts in evidence-based interventions.

This alternative perspective of arts-based interventions for trauma symptom management and healing calls for an examination of strengths present within Veteran trauma survivors, requiring a reframing of their symptomology. Using the arts (visual, literary, music, performance, etc.) as coping strategies in managing the aftermath of traumatic circumstances effectively serve as tools for learning to manage traumatic memories with a creative lens.

Using creative writing to process a Service Member or Veteran’s experience could be facilitated by understanding the three stages of the Hero’s Journey. This process can be done alone or with the guidance of a therapist. One could choose to write using a first-person perspective or use the voice of a third person to narrate the story of the “protagonist.”

The Creative Process

Before embarking upon the Hero’s Journey, it is highly recommended to ease oneself into the creative process by creating a specific space to brainstorm. One can compose music, create visual art, or even choreograph a performance piece using a creative process to begin using the creative lens to produce works in one’s chosen medium. The following process is outlined in Veteran Art Studio where one could use it alone or to assist a client:

- Find your favorite time, place, to create: Figure out where you feel the most comfortable to work on your chosen creative project. It could be a specific area of your home, outdoors, or even in bed using paper and pen or an app. Wherever you feel most inspired to create, go with it, and make it your creative spot.

- Choose your favorite method(s) to create: Whether you prefer using paper and pen, apps on your phone, voice to text, or a combination of a variety of methods, figure out what works best for you.

- Turn off your inner critic: You don’t have to be a published author or hold a Master of Fine Arts to get started, but you should do your best to silence your inner critic. It’s important to note that you shouldn’t get too bogged down in mastering the technical details of any medium or given craft. One can always adjust and correct later. Even the most experienced artists make mistakes, so allow yourself room for errors as well. The most important thing is that you’re here and expressing yourself.

- Figure out what you want to express most: Do you want to write about traumatic events? Do you want to paint a period that took place during childhood or adulthood – or even a combination of both? Decide what period you want to focus on.

- Outline your project: This is where you can start to organize a creative project by plugging in dates and locations of your story – or periods of time that inspire creative expression.

- Select a chapter or section that excites you the most and get to creating: Choose a specific event or details of your story that’s calling your name and go with it.

- Keep a notes app on your phone or a notebook for sudden bursts of inspiration: No matter what you like to use for planning creative projects, keep your preferred method for taking quick notes close. I prefer using both a notes app on my phone as well as a Moleskine notebook for random thoughts and unexpected moments of inspiration that I don’t want to forget. You’d be surprised how and when the muse strikes, so resist the urge to tell yourself, “I’ll remember this later.” Because inspiration comes and goes and can be easily forgotten.

The Hero’s Journey

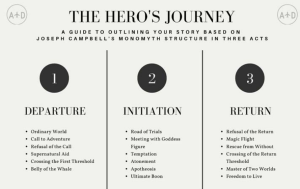

Author Joseph Campbell introduced the concept of the Hero’s Journey as a universal theme of going on a journey that includes a transformation.4 This journey is not only present in mythological tales and religious studies, but in well-known works such as Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and numerous other books and films. The book was intended to help people “see myth as a reflection of the one sublime adventure of life, and then to breathe new life into it.”

The challenging process of military-related trauma rehabilitation and community reintegration parallels Campbell’s metaphorical use via literary arts of the stages of departure, initiation, and return. The historical conceptual framework for understanding psychosocial and lingering impacts of trauma not only explains the odyssey of the Veteran experience, but that the path from trauma toward healing is a worthwhile journey that emerges from the creative process.

The Hero’s Journey may be used as a method for the writing process, but it is important to bear in mind that creative approaches are not limited to this medium. While narratives of trauma, military service, or even childhood can vary, it is important to choose a specific range of time to focus on one’s creative project. By selecting a specific period of time, one can concentrate on events, details, and themes that are linear and limited. In doing so, this minimizes distractions and tangents while giving the project its core.

The Three Parts of the Journey

The hero’s journey is broken down into three main acts or parts, with the bulk of the action happening in the middle of the story. Part 1 represents the departure of the protagonist, where the Servicemember or Veteran can begin their narrative as they prepare to embark on a journey or quest. Part 2 represents the initiation of the protagonist, who endures challenges, hardships, and undergoes a transformative experience. Part 3 represents the return, where the transformed protagonist returns to the so-called ordinary world where the story began.

Part 1: Departure

When writing, composing, or creating a project about war or major life changes, the concept of leaving the familiar behind is a common theme and a great way to introduce your audience into your world (or that of your protagonist should you choose a fictional character). One may use wartime deployment as an example of the hero’s departure. Consider incorporating the following six points to see how each line up with your creative timeline. If any point does not apply to your timeline, feel free to skip it.

- Ordinary World: Where you (the protagonist) are in your everyday life prior to receiving life-altering news.

- Call to Adventure: This marks the beginning of the quest, the first sign of stepping into the unknown and possibly a terrifying new path. For example, the first time you get orders and know you’re about to deploy.

- Refusal of the Call: Was there any reluctance or doubt about the journey ahead? This is where you address any resistance to upcoming changes or any challenges facing the main character before the journey begins. This could range from general anxiety to conflicts with family or loved ones prior to departure.

- Supernatural Aid: The main character receives help from an unlikely source or an important mentor before the journey officially begins. This is where you would introduce a key character in your story who may impact the hero or the journey in a deep, meaningful way.

- Crossing the First Threshold: The main character has accepted the quest – or in this case, come to terms with orders to deploy, and starts preparing accordingly. This could mark the pre-deployment phase.

- Belly of the Whale: The main character has officially crossed the threshold into another world. This could be where deployment officially begins, and the hero comes to terms with possible injury or death – of the self or comrades – physically and/or psychologically.

Part 2: Initiation

During this phase, the protagonist is tested on a variety of levels. This typically contains the bulk of your story, and where one or more climax / life-altering experiences will certainly take place.

- Road of Trials: The protagonist is tested for the first time with a challenge that proves to be a milestone in the overall journey. This can be the introduction of one or more traumatic events as they apply to your story.

- Meeting with Goddess Figure: Campbell referred to this point as when the protagonist manages to experience transformative love. This can refer to romantic relationships or a deep sense of camaraderie in the middle of conflict.

- Temptation: If the protagonist’s ethics and morals are challenged, a possible deviation from one’s path may occur. How does the protagonist respond to a crisis of conscience? This is another marker for traumatic events as moral dilemmas serve as important milestones to be discussed if they apply to your story.

- Atonement: The protagonist is confronted with challenges related to leadership and/or regret. In Campbell’s monomyth structure, this would be a point where the protagonist seeks forgiveness or guidance from a parental figure, mentor, or leader.

- Apotheosis: After a period of introspection, the protagonist reaches a point where fears are overcome in a new, profound way that indicates a loss of innocence and an increase in knowledge – for better or worse.

- Ultimate Boon: Having overcome traumatic events and survived, the protagonist becomes more aware of his/her own mortality. This is a space where survival is viewed as a leadership lesson, or a change in identity prior to the return. For example, redeployment or the end of one’s enlistment could be used as a milestone.

Part 3: Return

After multiple tasks are complete, the journey is nearing an end.

- Refusal of the Return: This is where the protagonist has a crisis of feeling unready to return – or redeploy. This could indicate a feeling of not having done enough or having done the wrong thing. There is a sense of incompletion – whether it pertains to a mission or the self – to be explored before the journey ends.

- Magic Flight: The protagonist is provided with some sort of assistance prior to the journey ending. This could be help from a battle buddy or a leader/mentor figure before the journey ends. This is where the protagonist reflects upon the entire journey before returning to the so-called ordinary world.

- Rescue from Without: The protagonist is trying to come to terms with being transformed by the journey and other characters in the story provide a degree of assistance – from friendship to advice – for the road ahead.

- Crossing of the Return Threshold: The protagonist is officially returning home – or redeploying. It is clear by this point that the journey has changed the protagonist, who is returning to the ordinary world as a different person, marked by life-altering events.

- Master of Two Worlds: This incorporates post-deployment processing and community reintegration. As the journey has changed the protagonist, there is a new, intersectional understanding of the world.

- Freedom to Live: This final point indicates lessons learns, a newfound knowledge, and a sense of having survived.

George Lucas claimed that using Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey structure was vital in his creation of Star Wars, noting it is a structure that is timeless and can be seen in stories and myths for thousands of years.5 I certainly agree that it is helpful as a structure to process one’s military experiences. This is intended to help organize one’s personal narrative as well as in discovering one’s authentic voice as an artist. Once this journey is completed, one will have a source to pull from and return to for creative inspiration that is completely organic and original.

The Arts and Healing

What led me to writing as Veteran after returning from the Iraq war? I was tired of living on a powder keg of my own trauma. Much like other trauma survivors, hypervigilance, anger, depression, and a variety of trauma-induced symptoms can take its toll on the psyche, and I found myself running on fumes for years in my own community reintegration process.

The purpose of writing one’s narrative or using another creative outlet to express emotion is not only to document aspects of one’s life, but to also make it tangible and gain perspective. When we’re given the space to breathe, create, and see or hear our work before our eyes, the results are a sense of empowerment and the gift of seeing or hearing our experience in present, tangible form. In turn, the writer owns those thoughts and memories – they don’t own the writer.

Expressing life experiences, whether through creative writing, painting, music, or performance art, has the power to alleviate many of what we might have been taught to suppress or numb out. Instead, I invite survivors to transform trauma into inspiration.

According to the American Art Therapy Association,6 arts-based interventions – from the visual arts to music – can be used to:

- Reduce PTSD symptoms and co-existing conditions

- Improve cognitive functioning and behavior

- Aid in the expression of traumatic events and addressing recurring episodes

- Bolster self-esteem and providing stress reduction

When it comes to creating music, the effects are quite similar. Music-based therapeutic interventions have demonstrated the ability to facilitate the expression of traumatic memories, resilience building, motivation for long-term success, and lowering the need to seek additional mental health services.7

Creatively Expressing Trauma

Dr. James Pennebaker, who studied expressive writing, said “By writing, you put some structure and organization to those anxious feelings,” and that “It helps you to get past them.”8 Other research by Dr. Pennebaker indicates that suppressing negative, trauma-related thoughts compromises immune functioning, and that those who write visit the doctor less often.

There is something undoubtedly special about putting one’s own thoughts and memories into a creative project. When we express what disturbs us the most, what we fear, or things we are afraid to talk about, we free up space in our minds for something positive and healthier to take up that space. If we become unafraid of the voices within, it is also easier to lose our fear of the voices of those around us.

In the book Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within, Natalie Goldberg states, “I don’t think everyone wants to create the great American novel, but we all have a dream of telling our stories-of realizing what we think, feel, and see before we die. Writing is a path to meet ourselves and become intimate.”9

Creativity Makes Life Worth Living

One of the most worthwhile aspects in the journey of expressing trauma is that we get to know ourselves that much better. Our voice and creative lens are important, not only to ourselves but to the collective story of humanity. It is easy to take that for granted. When we allow ourselves to speak from the heart and mind, we release a purifying fire onto the blank spaces before us.

When we transmute trauma into inspiration, it is somewhat of a magical process, much like the Hero’s Journey itself. Our perceptions change when we revisit past events – after we have changed, grown a bit older, and hopefully wiser. But more importantly they allow us to see memories in tangible form and provide space for reflection. By reflecting, we give ourselves both space and permission to let go of what has been hurting us or haunting us, and more importantly, we give ourselves the space to heal.

Campbell said, “My general formula for my students is, “Follow your bliss. Find where it is, and don’t be afraid to follow it.””10 In closing, I invite you to do the same. If you are a Servicemember or Veteran, create from your heart in a way that alleviates some of the burden from your own psychological ruck sack. If you are a clinician, help create the space for Veterans to do just that. More importantly, in creating works that emanate from difficult experiences, we create something new that allows us to follow our bliss toward a path of healing, redemption, and purpose.

References

- Campbell, J. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Vol. 17). New World Library. 23-28, 222, 271-73, 289-90.

- Dallocchio, M.B. (2017). The Desert Warrior. Latte Books.

- Dallocchio, M.B. (2020) Veteran Art Studio. https://www.youtube.com/c/MBDallocchio

- Campbell, ibid. 23-28.

- Vogler, C. (2017). Joseph Campbell goes to the movies: The influence of the hero’s journey in film narrative. Journal of Genius and Eminence, 2(2), 9-23.

- American Art Therapy Association. (2012). Art therapy, posttraumatic stress disorder, and veterans. Retrieved from: https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/RMveteransPTSD.pdf

- Bradt, J., Biondo, J., & Vaudreuil, R. (2019). Songs created by military service members in music therapy: A retrospective analysis. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 62, 19-27.

- Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162-166.

- Goldberg, N. (2005). Writing down the bones: Freeing the writer within. Shambhala Publications. xii, 11-13.

- Blessing, K. (2017). Cosmic Justice in Breaking Bad: Can Sociopaths and Antiheroes Lead Meaningful Lives?. In Philosophy and Breaking Bad(pp. 77-92). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Art Credits

All illustrations by M.B. Dallocchio, LMSW

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

M.B. Dallocchio is a London-based Chamorro artist, author, and social worker who specializes in artistic psychosocial rehabilitation. Dallocchio served as a medic, mental health sergeant, and retention NCO in the US Army for eight years. While on deployment to Ramadi, Iraq in 2004-2005, she served as a member of “Team Lioness,” the first female team that was attached to Marine infantry units to perform checkpoint operations, house raids, and personnel searches on Iraqi women and children for weapons and explosives.

In addition to having been featured in the San Francisco Chronicle, The Huffington Post, Las Vegas Review-Journal, PBS, Yahoo! News, and many other media outlets covering facing injustice during and after combat, she also speaks out on women and minority issues, post-traumatic resilience, and the importance of self-empowerment. She received her MSW from the University of Southern California and is a David L. Boren Scholar in Czech studies and international relations.

For more information, visit: https://www.thedesertwarrior.com/

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.