By Vicki Topaz, Filmmaker, Photographer and Daughter of a WWII Veteran

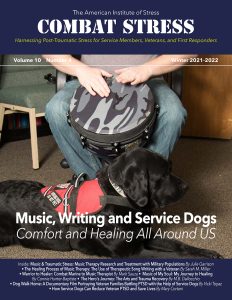

*This is an article from the Winter 2021-2022 issue of Combat Stress

Perhaps more than any other art form, documentary film has the power to make the unseen seen. As filmmakers, this is what we set out to do in Dog Walk Home: offer a rare glimpse into the lives of three Veteran families as they share their stories from the privacy of their homes. Through their voices we learn about the causes and effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in all its myriad forms: injury, assault, survivor’s guilt; anger, self-isolation, and self-medication. Yet these are not the places where we linger. The heart of this film is elsewhere: in hope, family, recovery, and the service dogs that help make it possible.

Why would these Veterans and their families allow our filmmaking crew of five into their homes? Why would they bare their souls to us? It is not complicated. These people are a different breed of Americans — those few who have pledged their lives to protecting their country and their fellow Service Members. If this film saves even one Veteran’s life or inspires one Veteran to seek help, the discomfort of sharing their stories will have been worth it. And thanks to the love of their families and some very good dogs, these Veterans have regained the heart to complete this vital mission.

How This Film Came About — and Why It Is Important to Me

All of my work with Veterans has been deeply personal — a truth which, over time, I realized was partially rooted in the formative experiences of my own childhood. My father was a U.S. Army Veteran who flew missions as a tail gunner in Europe during WWII. Like the Veterans in Dog Walk Home, he arrived home with PTSD, a condition that was unrecognized and untreated at the time. Now, all these years later, I know that he was grappling with PTSD which led to his anger and alcoholism. I also know that my childhood perspective has helped me foster deeper insights into the unique struggles of children and families living with trauma.

My desire to shed light on the Veteran experience began to take shape more than a decade ago, but it truly crystallized when I started interviewing and photographing Veterans living with PTSD for my multimedia project called HEAL! It was an honor and a revelation to listen to these Veterans relate their stories of military service, to learn about their subsequent battles with PTSD, and especially to witness how their service dogs helped put them on a path to restoring their independence.

Somewhere along the way, my thoughts circled back to my own childhood memories as I was gathering these intimate stories told in HEAL! I realized there was yet another facet of the Veteran experience that needed to be told: the role of the family. This insight ultimately led me to Dog Walk Home to show how PTSD impacts Veterans and also to reveal how secondary trauma impacts family members.

The Exceptional Families (and Dogs) in Dog Walk Home

The stories and perspectives of the three Military families in the film are unique, yet they all share a dual thread: their struggles with PTSD and secondary trauma and the discovery of dogs willing and able to meet them in their darkness and lead them into the light and love of family and friends.

We first meet Emilio Gallegos, a Mexican American U.S. Marine Corps Veteran, Purple Heart recipient, poet and single father. Speaking of his deployment in Iraq, Emilio describes how the Humvee he was driving on his base was blown apart by an improvised explosive device. Suffering with symptoms of PTSD and a traumatic brain injury, he returned home distant and angry, self-isolating from his own family and from the world. However, his isolation ends and reconciliation with his children begins when Emilio is partnered with his service dog, Samson.

Next, U.S. Army Veteran Kim Voss shares the heartbreaking account of how her PTSD first developed from early childhood abuse and was then compounded by a sexual assault in the military. Demoralized by “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” she left the service to manage her symptoms as best as she could. Just as her marriage to wife Tamara is hanging on by a thread, Kim is partnered with her service dog, Artemis. She helps Kim remain in the present and gives both Kim and Tamara the strength and stability to stay together.

Next, U.S. Army Veteran Kim Voss shares the heartbreaking account of how her PTSD first developed from early childhood abuse and was then compounded by a sexual assault in the military. Demoralized by “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” she left the service to manage her symptoms as best as she could. Just as her marriage to wife Tamara is hanging on by a thread, Kim is partnered with her service dog, Artemis. She helps Kim remain in the present and gives both Kim and Tamara the strength and stability to stay together.

And finally, we meet Ramon Reyes, a Mexican American U.S. Army Veteran who deployed twice to Iraq. He is haunted by survivor’s guilt and stricken with severe PTSD. Ramon self-medicates with alcohol to such an extreme that he temporarily loses his wife and two children. When he is treated at the VA and then partnered with his service dog Huey, Ramon can finally start mending the rift with his family. Huey helps everyone in the family lessen their symptoms of PTSD and secondary trauma.

The Human-Animal Bond: How Does It Work, and How Does It Help?

“When you’re looking at the entire scope of the human-animal bond, dogs are the gold medal winners. The chemistry and wiring of their social brain network is most similar to ours. This is why, neurobiologically speaking, dogs are our best friends!” — Meg Daley Olmert, film advisor and author of Made for Each Other: The Biology of the Human-Animal Bond.1

“Samson helps me decompress. I talk to him a lot too. When I’m at the store, buying cereal, I ask him, ‘What should we get today? What do you think? Maybe some Fruit Loops?’ People in the aisle are like, ‘Is that guy talkin’ to his dog?’ Having Samson gives me a chance to love someone every day. Sometimes I’ll step outside of the house, to run to my car quick, or go into the garage. When I come back in, he gets so excited, ‘Where did you go?’ I’m like, ‘Man I was just outside a couple of minutes.’ It’s easy to get lost in alone-ness but now, I’m not alone, I’m never alone, you know.”

—Emilio Gallegos, U.S. Marine Corps (1999–2010). Deployed to Iraq. Purple Heart recipient. Service dog and training provided by Operation Freedom Paws in 2016.

One of my first questions about service dogs was, how can they help reduce the symptoms of PTSD? The answer lies in their extraordinary ability to merge into our hearts and homes. They quickly become family and much more. Emilio Gallegos captured it when he said: “Having Samson gives me a chance to love someone every day.”

Like all good friends, they know us well — often better than we know ourselves. Their extraordinary sense of smell can alert them to the chemical changes that signal the onset of stress, anxiety and night terrors and pull their Veteran back from these emotional pitfalls and remind them they are safe and loved.

When Ramon Reyes first brought Huey home, there happened to be fireworks in the neighborhood. The explosions echoed Ramon’s wartime experiences, but Huey was able to detect his rising anxiety. By jumping on Ramon’s lap and licking his face, Huey created a distraction and prevented what would have surely been a triggering event.

When Ramon Reyes first brought Huey home, there happened to be fireworks in the neighborhood. The explosions echoed Ramon’s wartime experiences, but Huey was able to detect his rising anxiety. By jumping on Ramon’s lap and licking his face, Huey created a distraction and prevented what would have surely been a triggering event.

As Meg Daley Olmert goes on to explain in the film, the social brain network is also the anti-stress network. So, when we pet, hug, snuggle and sleep with our dogs we are producing the brain chemicals that ease the symptoms of PTSD.

These are just a couple of examples that show us how service dogs anchor their Veterans in the present moment.

“There are times that I push people away, especially when it gets close to anniversary dates of certain events that happened in Iraq. Huey won’t let me. He senses it. He’ll come up and start nudging at me like, ‘Hey, pay attention to me. Pet me.’ He won’t stop until I actually pay attention to him. Every time I say, ‘Leave me alone.’ He comes back and he’s at it again. He helps with fireworks too. The first night some fireworks went off, I got real bad anxiety. Right away, he jumped on top of me and started licking my face. I was so amazed. And still to this day if there are fireworks going on, he comes up to me.”

—Ramon Reyes, U.S. Army (1995–2012). Two deployments to Iraq. Service dog and training provided by Operation Freedom Paws in 2017.

The Impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 has put Veterans at increased risk. Forced isolation, stress, fear of the unknown, and suicidal ideation are just a few of the factors they face. Not to mention the very real risk for Veterans whose immune systems were compromised in the military conflicts in which they served. For this group, fear of contracting the virus can trigger a vicious feedback loop and cause even higher levels of stress and anxiety. In a Zoom recording with Ramon Reyes, he shared this comment: “The past couple of days I haven’t been able to sleep right. The nightmares have started. There are times that it takes me back overseas, just fighting an enemy we cannot see.” We were also able to record Emilio Gallegos via Zoom, and he shared this with us: “I see how it can go one or two ways: having comfort in it, because I’ve been here before emotionally and mentally, or having extreme discomfort, because this reminds me of a bad place. And I don’t want to be there again. You know what I mean?”

The film revisits each family post shut-down to see how they’ve managed the challenges of COVID-19 and to catch sight of what their futures hold. To no one’s surprise, we learn that Samson, Artemis and Huey continued to play a profoundly stabilizing role for the whole family as the pandemic played out.

Helping Veterans Succeed: Why Dog Walk Home — and Why Now?

“When the peace treaty is signed, the war isn’t over for the Veterans, or the family. It’s just starting.”2 —Karl Marlantes, author, Vietnam War Veteran, U.S. Marine Corps

How can we expect Veterans to smoothly reintegrate into civilian life when daily functioning is so difficult? Why do they wait so long before asking for help? And why do service dogs make such a positive difference?

The three Veteran families featured in Dog Walk Home are representative of the wider audience the film is made for. Namely, underserved Veterans and the communities that support them, including Latino, LGBTQ, and BIPOC groups as well as seniors, women, and disabled Veterans. An even wider audience of mental health workers, educators, and of course all dog lovers will draw their own meaning from the film.

The three Veteran families featured in Dog Walk Home are representative of the wider audience the film is made for. Namely, underserved Veterans and the communities that support them, including Latino, LGBTQ, and BIPOC groups as well as seniors, women, and disabled Veterans. An even wider audience of mental health workers, educators, and of course all dog lovers will draw their own meaning from the film.

Further, by holding up a mirror that reflects hope back to other Service Members and families who face similar challenges, we believe Dog Walk Home can offer a roadmap and urge them to seek help.

It Takes a Village (to Make This Film)

Telling such stories through the medium of film is, to say the least, a collaborative process. Years before Dog Walk Home began to take shape, I was introduced to Mary Cortani, herself a Veteran and Certified Army Master of Canine Education, and the founder of Operation Freedom Paws (OFP), a nonprofit that partners Veterans with service dogs. It is thanks to her that I had access to the Veteran community served by OFP. Being among them and hearing their stories opened my eyes and my mind to a world I had been seeking. I am so grateful for the many trusting relationships with Veterans and their families that I developed over time.

To help share these stories of trauma and healing, I joined forces with a like-minded filmmaker, Wynn Padula. Wynn collaborated with Iraq War Veteran Bobby Lane and other Veterans with disabilities when he codirected and shot Resurface, an award-winning Netflix original short documentary about the healing power of surfing for Veterans traumatized by PTSD.

The stories of Dog Walk Home are augmented with critical “how and why” insights from experts in the science of the human-animal bond, trauma specialists, and service dog training professionals. They help explain what we see and hear from our Veterans and their families about the healing power of their service dogs featured in our film. We will also get a better understanding of why the Veterans Administration has been reluctant to fund service dogs to those with the “invisible wounds” of war and the progress that is now being made.

The stories of Dog Walk Home are augmented with critical “how and why” insights from experts in the science of the human-animal bond, trauma specialists, and service dog training professionals. They help explain what we see and hear from our Veterans and their families about the healing power of their service dogs featured in our film. We will also get a better understanding of why the Veterans Administration has been reluctant to fund service dogs to those with the “invisible wounds” of war and the progress that is now being made.

To see the full lineup of our remarkable and dedicated crew and film advisors, please visit our website at Dog Walk Home. The film is currently in production with an anticipated release date in 2022. This project is made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“Artemis has affected my entire life, both going out in public and being at work. She’s also helped my marriage quite a bit—I’m able to be present a lot more. I don’t stay locked in my head as much. Artemis helps all of us be aware of when I’m feeling particularly anxious or when I’m feeling angry. Having a service dog is an incredibly vulnerable thing because you can’t just hide your feelings and emotions because these darn dogs, they know, they can smell it, they can feel it. Artemis helps make me more aware and more accountable for who I am and how I show up in the world.”

—Kim Voss, U.S. Army (1989-1993). Military Intelligence. Service dog training provided by Operation Freedom Paws in 2019.

View a short 3-minute sample trailer for Dog Walk Home: https://vimeo.com/386530510

We are devoted to telling these stories of healing and transformation to prove to Veterans and non-Veterans alike that recovery is possible for those who seek help. If you are reading this right now, we are thankful to have reached you.

Contact: Vicki Topaz, San Francisco, CA, email: [email protected], text: 415-298-9465

References

- Olmert, M.D. (2009). Made for Each Other: The Biology of the Human-Animal Bond. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Marlantes, Karl (2011). What It Is Like To Go To War, New York, NY, Atlantic Monthly Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Vicki Topaz has worked as a photographer for the past 25 years. Since 2010, she has focused on a multimedia project called HEAL! This endeavor documents Veterans sharing stories of their military service and their struggles with PTSD — as well as the service dogs who provided lifesaving aid. Her short documentary Veterans Speak About PTSD garnered significant public attention and was screened in 17 film festivals nationwide. Her deep, personal commitment to telling these stories is rooted in her childhood experiences with her own father, a WWII tail gunner who returned home with PTSD, which was then unrecognized. Prior projects include SILVER: A State of Mind, a photographic series about women and aging that was exhibited at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging and featured in the New York Times, the Times of India, NPR’s Forum, and other international news media. Her 2008 monograph Silent Nests depicts the first photographic investigation into the medieval dovecots of Normandy.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.